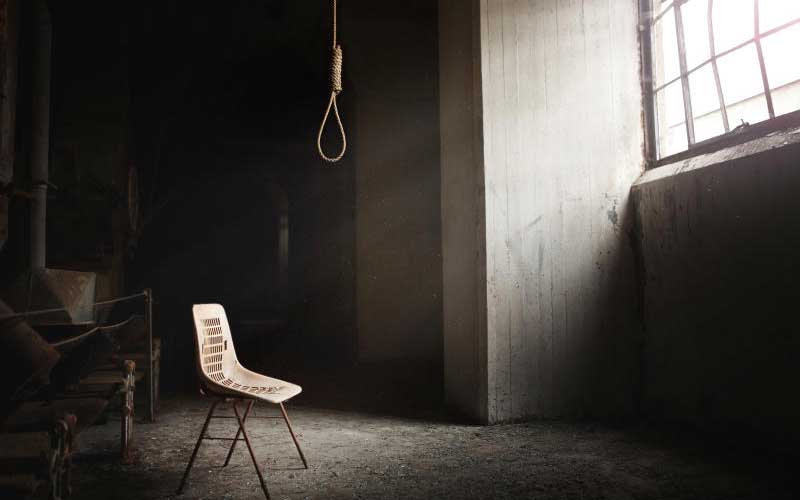

Do you get the impression that there’s more depression and suicide among children these days, especially teenagers? It’s true, there is. All around the world surveys report a growing sense of despair among young people, and rising numbers of suicides.

Because it’s not only adults who get depressed. So do children and teenagers. Unfortunately, childhood depression, especially in teens, can be difficult to spot. Because all kids get low or moody from time to time. But childhood depression’s different from those ‘normal’ blues. It’s not a passing mood, and it won’t go away without help.