×

The Standard e-Paper

Join Thousands Daily

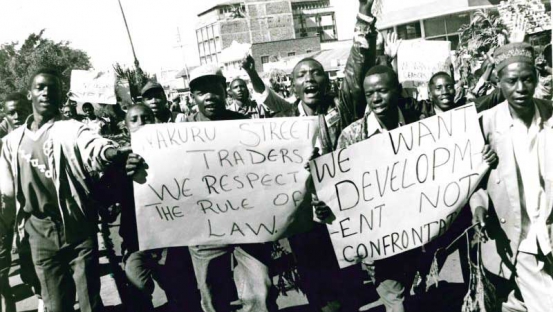

After decades entrenched in mistrust and ethnic hatred, two key events in recent history were expected to foster unity and cohesion. And they did. For a while.

The advent of multi-party democracy and the promulgation of a new Constitution, though 20 years apart, did promote unity, cohesion and economic development.