×

The Standard e-Paper

Kenya’s Boldest Voice

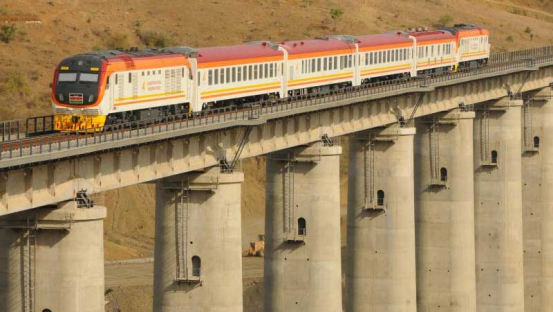

News that Kenya would increase its debt stock with China after securing a Sh370 billion loan to extend the Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) from Naivasha to Kisumu is sobering.

China’s debt to Kenya now stands at more than Sh2 trillion, with the SGR alone taking up Sh847 billion. The second-largest economy in the world has surpassed other top external lenders such as Japan, France and Germany to establish itself as Kenya’s biggest bilateral lender.