×

The Standard e-Paper

Kenya’s Boldest Voice

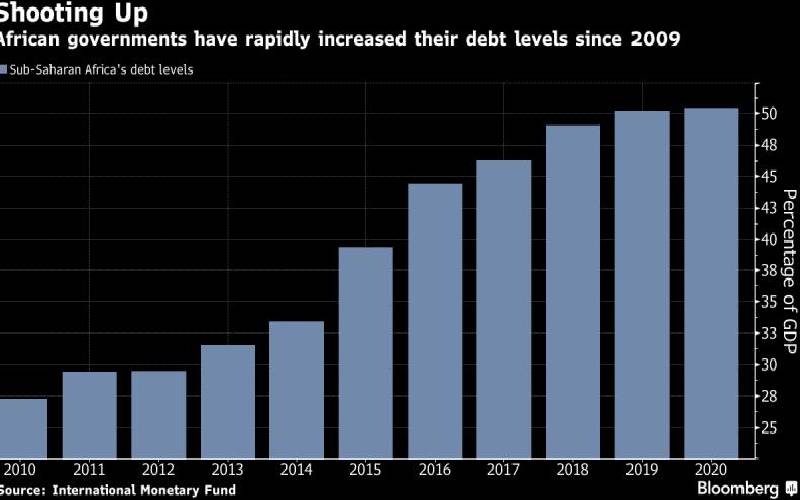

African governments have rapidly increased their debt sine 2009.

The costly Eurobonds and multiple Chinese loans have come back to haunt the Jubilee government in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic.