×

The Standard e-Paper

Kenya’s Boldest Voice

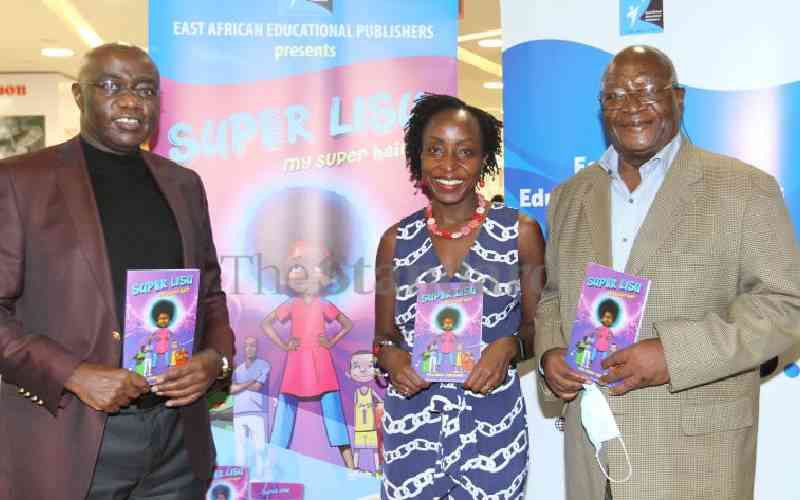

East African Educational Educational Publishers (EAEP) CEO Kiarie Kamau (from left) author Yolanda Chakava and EAEP Chairman Henry Chakava during the launch of 'Super Lisu' book at Sarit centre,Westalnds, Nairobi. [File,Standard]

I met Henry Chakava, who passed on Friday, in September 1986. I had recently graduated from the University of Nairobi for the second time in three years.