×

The Standard e-Paper

Fearless, Trusted News

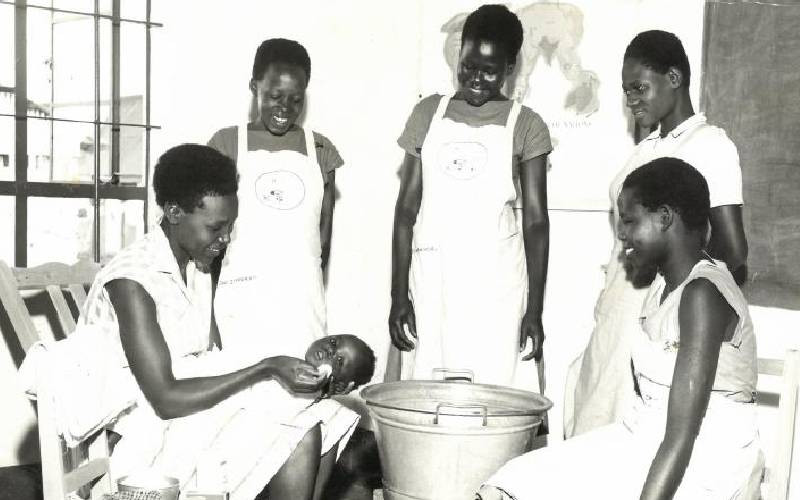

Health worker Grace Ogot (left) training mothers on maternal child care in Kisumu in June 1963. [File, Standard]

The absurdities of our times! Although the country is still struggling to achieve gender parity more than a decade after the entrenchment of this right in the Constitution, Kenyan women have faced worse treatment in the past.