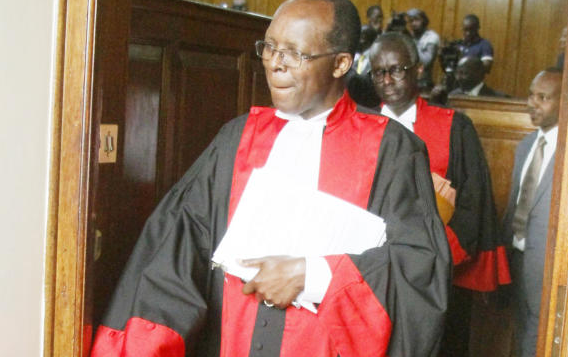

After a stellar career in law that culminated in his appointment as a justice of the Supreme Court, Prof JB Ojwang now faces the risk of an ignominious exit, after an audacious decision by the Judicial Service Commission (JSC) to commence removal proceedings against him for alleged gross misconduct.

Ojwang may have played a role in compounding his problems when he declined to meet with a committee of JSC to provide his viewpoint regarding the gross misconduct complaint. Instead, he wrote an impudent letter to the JSC, in which he claimed that there was “ill-intent against him” presumably from the “well-known committee,” and that for this reason, he would not be meeting them. The refusal to go before the committee, and also the haughty manner in which it was expressed, left the JSC with little choice but to refer the matter to the President.