×

The Standard e-Paper

Kenya’s Boldest Voice

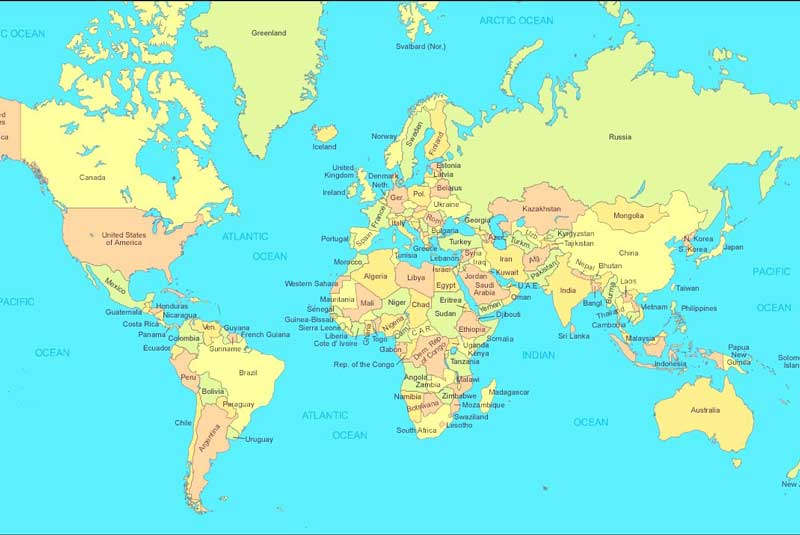

There are signs that while three powers remain dominant at the geopolitical top, several other powers are struggling to occupy or remain in the second tier slot. Those in the top tier are the United States whose hegemonic global presence is eroding, Russia, recuperating from the disasters of post-Soviet realities, and Communist China whose apparent “grand strategy” is to draw the rest of the world to the middle kingdom. Before 2016, the European Union could have fitted in the top tier, but it is fragmenting from within.