×

The Standard e-Paper

Stay Informed, Even Offline

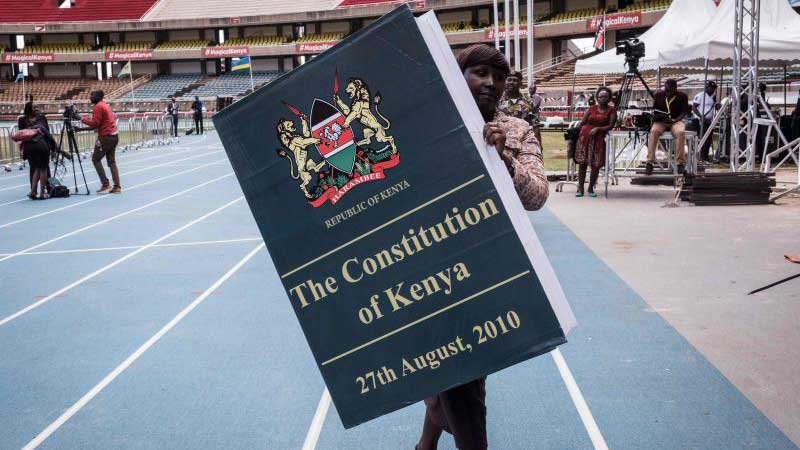

There is now general consensus that the Constitution needs to be reviewed. Some will argue that this consensus was manufactured by the political elite. At this stage, that is a moot point for in any case, we need to audit the Constitution as a bare minimum. Yet as we embark on this journey, we need to bear a number of things in mind.