×

The Standard e-Paper

Stay Informed, Even Offline

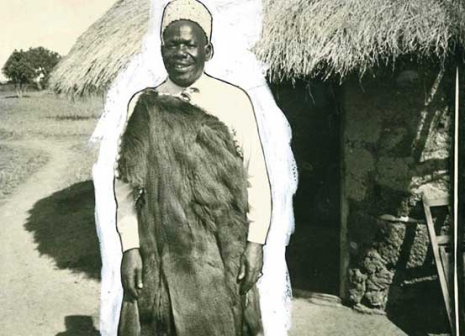

Every morning when Elijah Wafula, 77, wakes up, he heads to his father’s grave and gives it a good scrub.

He then lays out the visitors’ book on a stool at the corner of the room and delicately places a pen on it waiting for the day to break.