×

The Standard e-Paper

Fearless, Trusted News

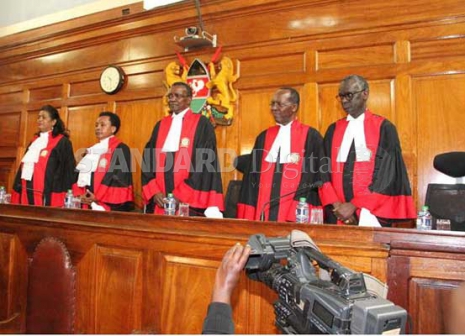

There is no doubt that Kenya’s Supreme Court made a historic decision in annulling the country’s August 8 presidential election. But it has been met with mixed reactions.

There are those who see the decision as a success for democracy and the epitome of constitutionalism, in particular the separation of powers. Others view it as a subversion of democracy and a mutiny on the rights of the electorate.