×

The Standard e-Paper

Kenya’s Boldest Voice

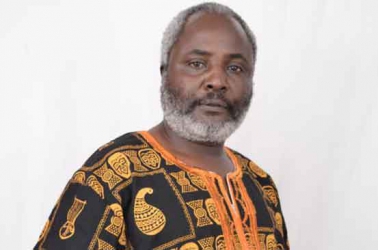

Goro wa Kamau’s appearance shouts ‘beware, Professor on the prowl’ even before he speaks. Yet his easy-going manner sets you at ease. “I don’t think I have a reasonable answer why I write,” he says and busts out laughing when I ask him why he writes.

“I think I write because I must. If you are meant to write, I don’t think you have much of a choice in the matter. Then when I look around me, I see so many stories that need to be told.”