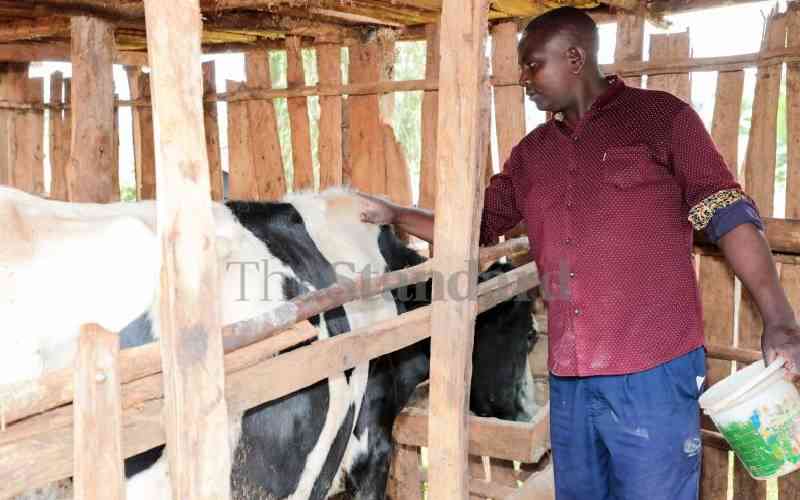

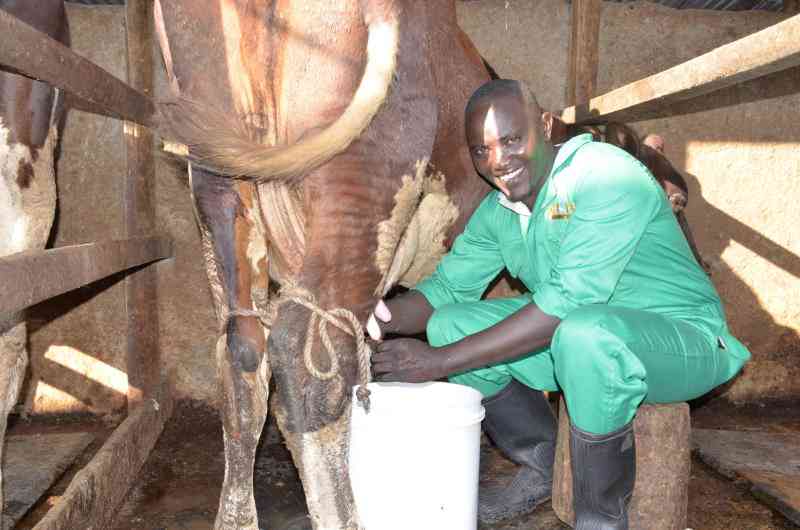

A few weeks ago, Smart Harvest did a story on how tsetse suppression in Embu area has directly contributed to increased milk production due to significant reduction in the prevalence rate of nagana in livestock.

Nagana is a fatal animal disease, which has a negative impact on livestock and crop productivity and thus food security among the affected communities.

Nagana is caused by protozoa, and in Africa is mainly spread by tsetse flies but can also be spread to a lesser extent by other biting flies and even surgical instruments. The presence of tsetse flies in an area will thus correlate with high cases of nagana.

Presence of tsetse flies will render an area uninhabitable to man and animals; as a result locking out man from cultivating the land and denying animals grazing lands. In addition, sick bulls cannot be used to plough land. It is for this reason that tsetse flies are documented in historic books as a force behind human migrations.

In Kalenjin, tsetse infested areas are referred to as ‘Nyalili Buch’, which means good for nothing and this is in reference to the green pastures taken over by tsetse flies.

Nagana is derived from a Zulu word N’gana which translates to powerless or useless; a connotation of what the disease does to animals. It is worth noting that nagana is the animal form of trypanosomiasis which is a disease of both man and animals. The human form is called sleeping sickness but for this article we shall discuss only the animal form – nagana.

Endemic zones

Nagana affects cattle, horses, dogs, pigs, donkeys, sheep and goats. But most farmers are familiar with the disease in cows; this is attributable to the fact that tsetse flies have a preference for cow blood meal; in effect, cows serve as a barrier to other livestock in a herd. The other reason could be the importance of the cow in most livelihoods in tsetse endemic zones.

The disease takes two forms namely a short and long form depending on how the disease progresses and eventual death where it is not managed appropriately and timely.

Animals will become infected by nagana following a bite from an infected tsetse fly and the first signs will appear after 11-21 days. These signs will include a relapsing fever, copious tears, dullness, loss of appetite and restlessness. These are unspecific signs and can only be used to give a tentative diagnosis. More specific signs for nagana will be observed in chronic cases and include swelling of the lymph nodes; reduced production of milk and abortions in females, the bulls will grow weak and can no longer mount females. If not treated death occurs.

Although there are few drugs in the market for nagana; with proper diagnosis, appropriate and timely treatment rate of healing is quite good. The best way to prevent nagana in Kenya is through vector control. The tsetse fly is a weak insect, which is easily killed by synthetic pyrethroid insecticides. Research has shown that if 80 per cent of farmers in a given area spray their animals with these insecticides for only six months, they can reduce tsetse population almost to zero. The efforts by the Kenya Tsetse and Trypanosomiasis Eradication Council, which is spearheading the eradication of tsetse flies in Kenya must be lauded and with good government support the country can get rid of tsetse flies and save farmers from the negative effects on their livestock.

The writer teaches Agricultural Information and Communication Management at the University of Nairobi

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.