South Sudan’s oil fields have become a battleground in the struggle for power in Africa’s newest nation. This has seen Western nations and regional mediators consider international monitoring of crude revenues as a way to remove a major bone of contention from such conflicts.

South Sudan sits on Sub-Saharan Africa’s third-biggest crude reserves. Its oil fields were early targets in fighting that erupted in December and has rumbled on despite two ceasefire deals and UN warnings that a man-made famine looms.

It marks an alarming slide into dysfunction by a nation whose creation three years ago was hailed a foreign policy success. Instead of lifting the nation out of grinding poverty, oil is blamed for stoking a war.

“If there is a clearer control of oil revenue, that may remove from the table one of the incentives over which people are divided or will fight,” said one senior Western diplomat close to the peace talks being held in the Ethiopian capital.

“How do you turn the resource question into a confidence builder as opposed to a conflict creator? That’s the challenge in negotiation.”

Monitoring could range from putting oil earnings into an independently managed escrow account — which South Sudan rebel leader Riek Machar called for — to less intrusive mechanisms where allocations of revenues were checked.

The mechanics

Diplomats and regional mediators said monitoring revenues was gaining traction as an idea for discussion, though the mechanics of such a system and how the warring sides would be pushed towards a deal have not been determined.

“Monitoring of oil revenue is being discussed,” said another Western diplomat, “but the details would need to be worked through.”

South Sudan’s oil output has tumbled by about a third to 160,000 barrels a day since the fighting began in December, but it remains the main source of cash for President Salva Kiir’s government, both by selling crude and by borrowing against future earnings, digging the nation deeper into debt.

As of June 25, South Sudan owed $256 million (Sh22.5 billion) to China’s National Petroleum Corp, which has 40 per cent of a venture developing South Sudan’s oil fields, and a further $78 million (Sh6.8 billion) to oil trader Trafigura.

It plans to borrow about $1 billion (Sh87.8 billion) from oil firms in the 2014/15 fiscal year, equal to about a quarter of forecast revenues.

Violating sovereignty

Rebel leader Machar, who was fired as deputy president last year, said oil sites would be a “legitimate target” unless funds were put into a neutral escrow account pending any deal.

But President Kiir’s government says such outside intervention would violate its sovereignty.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

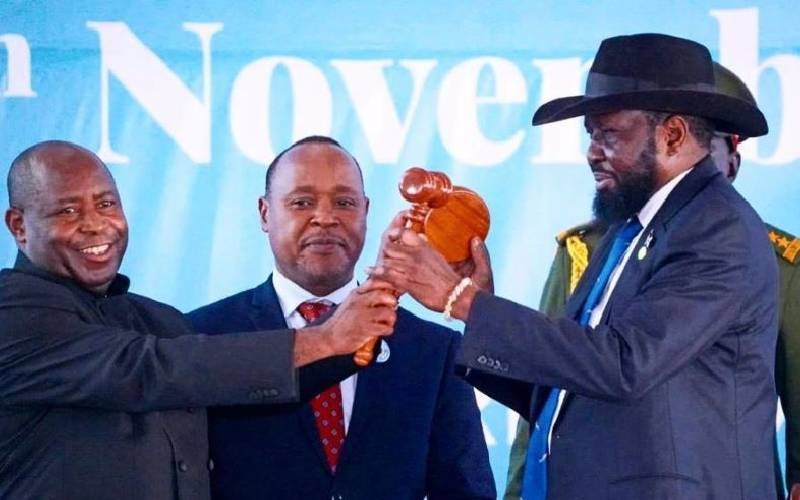

Kiir and Machar come from rival ethnic groups, and the conflict has re-opened deep ethnic divisions in the country.

Monitoring revenues is on the table for talks sponsored by the regional African grouping Igad, though diplomats acknowledge it can only be part of a broader deal on how to share wealth and power in the divided nation.

“This is one of the points of the agenda that has been put forward by Igad negotiators, that is the management of national revenue and national resources,” Smail Chergui, the African Union’s commissioner for peace and security, said.

“When the two parties will achieve that level of advancement in the negotiations, this [agreement] might come. It has the support of the international community.”

South Sudan has already lost billions of petrodollars in its young life. Kiir wrote to 75 former and serving officials in 2012 seeking the return of $4 billion (Sh351.1 billion) that has disappeared since 2005. No significant amounts were repaid, diplomats said.

The country has almost no roads and only a third of its 11 million people can read. Fighting has killed at least 10,000 people and displaced 1.5 million.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.