The old man saunters into the room with the help of a walking stick with several aides in tow. The better years are obviously behind him and all that remains of his high profile life as the world’s top diplomat are sweet memories.

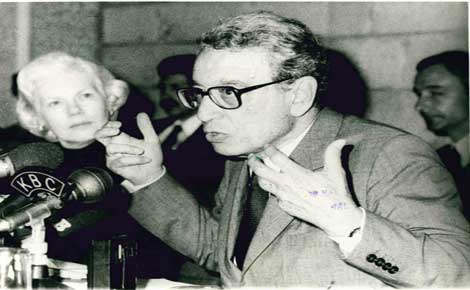

However, when he opens up to speak, Dr Boutros Boutros-Ghali comes alive — with his legendary baritone and commanding voice. Except for his now smaller frame and wrinkled face, the 91-year old still comes through as a witty and well informed diplomat, same as in the 90s when he served as United Nations’ sixth Secretary General.

This writer caught up with him last weekend in Cairo, Egypt, at the National Human Rights Centre where he serves as Honorary Chair.

That is just one of the many part-time duties of Africa’s first UN boss, who owing to his illustrious Political Science and International Relations background also lectures in a host of universities in Cairo.

So when The Standard On Sunday came calling, Dr Boutros-Ghali was open for conversation. The former UN boss, who speaks a bit of Kiswahili, is particularly cautious about Kenyans, whom he regards as politically alert and sensitive.

“When, for instance, I created the River Nile States Caucus in the 90s to address friction among nations over this giant water source, I looked for an appropriate African name and settled for “Undugu”. But the leadership of President (Daniel arap) Moi bitterly protested at the name, claiming it denoted communism,” he recalls.

The Egyptian diplomat was initially taken aback by the lamentations of Moi, whom he fondly refers to as “my age mate”. Dr Boutros-Ghali was initially excited with the name “Undugu” because it meant brotherhood — the very cord that he wanted to strike among the relevant countries that share the River Nile.

But in an effort to downplay tensions over a “mere name”, Dr Boutros-Ghali says he let go the “Undugu” name and later learnt that Kenya was uncomfortable with it owing to ideological differences with Tanzania.

Perhaps because of Kenya’s heightened political alertness and sensitivity, the country was plunged in the bloody 2007 post-election violence.

Dr Boutros-Ghali highly regrets the development but even in retirement, the one-time world’s top diplomat is heavily guarded on the issue as he is not willing to point accusing fingers.

However, he has a blanket statement on the matter: “Unfortunately literacy levels in Africa remain low, and coupled with poverty, our electorate are easily manipulated by politicians.

“Look at the case of Rwanda where ethnic animosity caused bloodshed. The same was to follow in Kenya and we must face and overcome tribal conflicts on the continent.”

Nonetheless Dr Boutros-Ghali hails Moi, who turned 90 this year, for peacefully handing over power on completion of his final term in office.

Even then, the former UN boss hits out at other African leaders for not giving democratic elections in their countries a chance, thus giving room for political revolutions.

He cites Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe and Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi, “who was President until he was killed in office.”

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

Except for Mugabe and Gaddafi, Boutros is heavily fascinated by Africa’s pioneer leaders, particularly Kwame Nkurumah of Ghana, Julius Nyerere of Tanzania, Kenya’s Jomo Kenyatta and Zambia’s Kenneth Kaunda, for their Pan-African approach in pushing the case of the continent.

And without mentioning names, Dr Boutros-Ghali condemns the new crop of our African presidents for being more interested in nationalistic than continental approach.

“Tomorrow’s problems bedevilling Africans will not be solved at the national level but at the international platform,” he contends.

Upon being reminded that some of the new leaders are reviving the old Pan-Africanist approach to confront the continent’s challenges and push for a stronger say at the UN (Security Council,) he lets out a sigh of relief. According to Dr Boutros-Ghali, who is also a political scientist and expert on International Relations and Law, the critical issue at hand is not about Africa having a permanent seat at the UN Security Council. “The real impediment is the existing UN system. At inception, the UN was constituted with just 50 nations in mind, but now there are over 300 nations in the world and we accordingly need overhaul the system with regard to its operational framework.”

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.