In my recent article, I presented a history of book banning and burning, and argued against it under any circumstances. But the censorship of literature is not always so total.

It can be more subtle and, in many ways, as a consequence, more sinister. However, subversive artists can find ways to turn such censorship on its head.

Let’s consider various forms of expurgation, or the removal of sensitive parts of a text from publication.

Again, such sections are invariably considered ‘sensitive’ for sexual reasons, or because there’s swearing, or for reasons of ‘national security’, that term, which oppressive governments employ whenever they don’t want embarrassing information leaked.

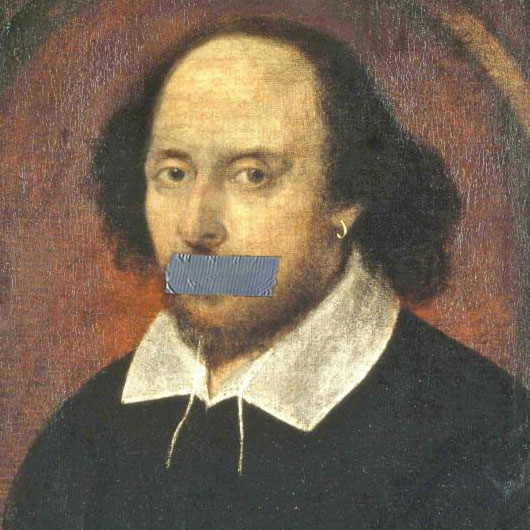

Possibly the most ridiculous (to us, today) examples of expurgation were performed in early 19th Century England by Thomas Bowdler, who published a version of Shakespeare’s Complete Works that would, he felt, be suitable for ‘women and children’.

Sanitised reworkings

There was little debate over whether women did require more ‘wholesome’ versions of the plays, for it was taken as sexist given by many that women could be easily offended, even corrupted, by the use of words like ‘damned’ or by prostitute characters.

In 1807, Bowdler published his reworked version, changing implications of suicide to read like accidental deaths and changing all instances of the exclamation ‘God!’ to ‘Heavens!’

He unwittingly left a name for this practice of taking a prudish editorial hand to texts: ‘to Bowdlerise’.

While we might, nowadays, giggle at Bowdler’s Puritanism, we experience something almost identical in the realm of television.

DSTV subscribers will, for instance, be used to all mentions of ‘God’ being bleeped out from films, denying viewers the choice to hear films as they were intended. Such expurgations happen in popular music, too.

James Blunt’s irritatingly twee song of a few years ago, ‘Beautiful’, had two versions, one with the lyric ‘I was f**king high’, and an alternative radio version with the replacement lyric, ‘flying high’.

Similarly, I was listening on Kenya’s X-FM last week and some song whose name I have forgotten, had the lyric ‘I’ve had a sh*t day’ dubbed so that the word ‘sh*t’ can’t be heard.

Even in my renditions of the lyrics here, with those inserted asterisks/stars, I’m indulging in modern Bowdlerism, as if readers of The Standard on Saturday can’t cope with the f-word and the sh-word.

Such sanitised reworkings of books are often called ‘fig-leaf editions’, as if they’ve had their offending parts covered up or removed, as would happen in old statues or paintings of, say, the naked Adam and Eve.

A problem with Bowdlerisation or any form of expurgation is that it treats the reading public as children, incapable of making our own choices about how to interpret texts.

To use a very British phrase, it smells of the ‘Nanny State’. Arguably, the publication of security documents that have had ‘sensitive information’ blacked out or redacted is an offense against democracy and implies that we, the citizens of a country, do not have full rights to information regarding how our government works.

And Bowdlerism makes great assumptions; that, for instance, we will be offended and, therefore, need advance protection in line with what has been called the ‘precautionary principle’.

Almost certainly, it would be better for us to be offended and then, ourselves, raise our concerns to those who write or publish, rather than having faceless publishers and editors restrict our access to full texts.

Political correctness

Finally, expurgations or redactions often make us the victims of other groups’ prejudices. For example, those DSTV omissions of the word ‘God’ (even when it’s not used as an expletive) are almost certainly the result of particular faith groups’ lobbying, but why should people who are not offended by innocuous mentions of the word ‘God’ be held hostage by a few who are?

And yet, the issue is not quite that simple. For example, what some right-wing commentators simplistically dismiss as ‘political correctness’ (that is, the move in the late 20th Century to revise how we speak of often disadvantaged or discriminated-against others) has great value, and shouldn’t be ridiculed.

The African American community in the US, and the black population elsewhere, rightly argue against the use of the word ‘n*gg*r’ by people from other communities, and this because of the appalling historical offensiveness of this word and the wider racism that accompanies its present-day use by ‘whites’.

The literary world has, as a consequence, seen old book such as Joseph Conrad’s ‘Nigger of the Narcissus’ retitled to ‘Children of the Sea’ or ‘The N-word of the Narcissus’, sometimes with all mention of the N-word removed from the interior text. Debate still rages as to whether such revisions are negative censorship or not, even amongst those who share the same broad political views.

Racist commentators

Most commentators, unless they’re racist, would nevertheless agree that modern literature should be written to avoid terms of abuse such as the N-word, ‘spastic’ for disabled people, and so on.

Is this self-censorship, or is it rather part of society’s move to reform itself into a more responsible way of building relationships between people? I’d argue the latter, although sometimes it’s tricky to know exactly where the line between the two lies.

But expurgation can sometimes be clearly positive and radical for a productive cause, say in the form of ‘erasure poems’, in which existing texts such as newspaper articles about government crimes have words and phrases (for example, politicians’ names) blacked out for satirical effect, or even just for artistic play.

Such erasure poetry stands on the mid-line between imaginative creativity and found or ‘chance’ poetry, and as such, participates in the debate over whether literary creation is, say, a gift of inspiration on the one hand, or, on the other, the mere inter-textual reordering of existing language.

Certainly, Bowdlerism and other forms of ‘subtle censorship’ of texts raise all manner of questions that it is your place, dear reader, to resolve; I shouldn’t control your interpretation.

My final word: I hope my editor doesn’t edit this article!

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and

international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and

international interest.