Kenya is charting a fairly new journey after discovery of coal in the Mui basin, rare earths in Kwale and oil in Turkana.

The country has not been a key player in this sector, which explains the rather feeble laws to regulate the sector. This calls for a serious review of the mining laws to ensure the country and the locals get a fair deal in the expected windfall.

The Government must put public interest first in developing the framework for the exploitation of these resources.

In the past, public interest has been overlooked as shadowy entities seeking to benefit at the expense of the country and the citizenry, run the show.

There have been cases of wheeler-dealers holding mining permits purely for speculation. It is not a secret that the mining blocks for oil were first handed over to political bigwigs for a song before they sold them to oil exploration companies, in the process making astronomical profits. Cortec Mining, for example claims that it has found rare earth minerals worth over Sh5 trillion. How did it arrive at this?

Clearly the Government needs to streamline the mining sector operations have been shrouded in secrecy.

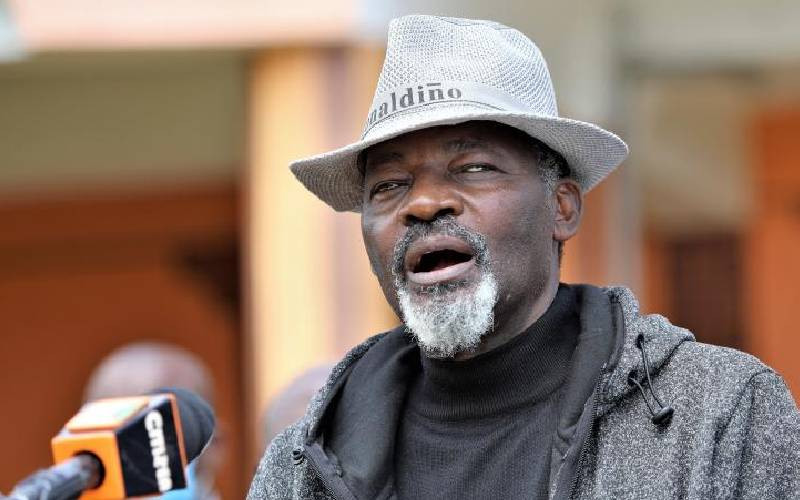

In trying to do so, Mining Cabinet Secretary Najib Balala cancelled 42 mining licences that he says were irregularly allocated. However, businessman Jacob Juma has thrown a spanner in the works by sensationally claiming that Balala solicited a bribe of Sh80 million so as not to cancel a licence for Cortec Mining Kenya to mine minerals worth billions of shillings in Kwale.

The accusations are weighty and as has happened in the past, talk around this matter will most likely produce more heat than light as political protagonists take hardline positions.

We are of the opinion that even a whiff of scandal touching on a Cabinet Secretary is bad enough. President Uhuru Kenyatta must get to the bottom of this matter.

Although Balala remains innocent unless proven guilty, it must never be business as usual because the new Constitution raised the bar on leadership.

When drafters of the 2010 Constitution envisaged a Cabinet devoid of politicians, they wanted well-grounded technocrats to speed up development. They reasoned that professionals not entangled in the murky world of politics would not be easily tempted into making quick money through corrupt dealings.

And because Government spending sets the pace for economic growth, a professional Cabinet was thought to be the best antidote to distorted progress. This way, Kenyans’ living standards would get an appropriate shot in the arm.

The Jubilee Cabinet is the first under the new constitutional dispensation and Kenyans’ expectations are so high, that the 18 men and women must be above reproach. They must be above the fray of politics and wheel dealing associated with past Cabinet ministers.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.