Kenyans usually admire the discipline, the decorum, self-respect and sense of purpose that students and former students of Moi High School Kabarak exhibit. What they do not know, however, is that the arduous task of ensuring that the boys and girls become responsible members of the society has always belonged to deputy principals. In the 40 years of the school’s existence, different deputies employed different tactics to ensure the teenagers did not run wild and to give the society men and women of good character.

They all succeeded in this endeavour in their own small ways. But perhaps the man who had runaway success was Joseph Rop who served between 1996 and 2001. Mr Rop was the Patrick Shaw of Moi High School Kabarak. The teacher, according to students, would be everywhere at the same time. He would be spotted in different places hundreds of metres apart at the same time—day and night. Omnipresent.

That is the term students used to describe him. Stories about his escapades by his students are hilarious but those who fell afoul with him still shudder at the mention of ‘Mnyama’. Rop earned himself the nickname for the brutal manner he dealt with ill-mannered students. Afterwards as sheng took hold of students, they turned to Mnyake and then Mnyaks. But despite the name change, his viciousness remained constant.

The deputy head teacher employed all manner of tactics to catch the criminal’s, as he referred to school law breakers. From putting on the school blazer camouflage to climbing atop trees and pretending to be the school’s ambulance driver, there was no knowing what shape Mnyake or what direction he would come from. “He would camouflage by putting on school blazers at night and walk close to or even join students planning mischief.

He would take his time and finally pounce on the ring leader dispersing others who would flee in different directions,” recalled Joshua Boiwo. Even in the most unexpected places, Rop’s presence was always felt. In the dorms, in the halls, in the school orchard, by the fence and kitchen you were sure to find Rop. The teacher had the patience and agility of a ravenous leopard lying low, firmly holding its breath with paws stealthily aching for a swoop and eyes firmly fixed on the prey as he tactfully hunted for mischievous students. Not even his oversize coats or even his well-built body could betray his presence. Everything within the school compound seems to have worked in favour of his camouflage mission. But boys will always be boys. We still engaged in mischief and sometimes escaped Mnyake’s hawk-eye.

Such mischief would include sleeping under the bed to avoid going for morning prayers or morning preps, winking at female students and sleeping in the chapel as the service went on or even not putting on socks or wearing only one for the fun of it. But woe unto you if Rop smelt your mischief. He would run after you, get hold of you and rain numberless blows on you until you screamed loud, attracting the attention of the whole school. And once the other students confirmed someone was being disciplined by Rop, they would disperse at the speed of light to avoid being roped into the mess.

Among the most serious crimes in Kabarak then were trespassing/stepping on the manicured lawns, failing to switch o lights by 11pm, being unkempt and missing the morning prayers. Rop, having studied the behaviour of students, knew that trespass mostly happened after 9pm. He would climb up a tree and wait patiently for the offenders. One day as we rushed to the dormitories to make ‘strong power’ after evening preps before retiring to bed, we used the forbidden shortcut as usual. As we passed by one of the trees, Rop lept from the branches and got hold of one of us— just one. The others rushed to the dormitories and buried themselves under blankets.

The next day, we came across the unfortunate boy, his face swollen from the many blows he received. Needless to say, the boy never used shortcuts again. Rop was a very patient hunter. There was this boy who rarely went to bed by 11pm as the school rules dictated. He would go out to a place he only knew and return late in the night. One day he did the same and when he returned was surprised to find someone sleeping on his bed. But before he could say Jack Robinson, the man sprung up and beat him senseless.

The boy later discovered that Rop was the intruder who had taken over his bed, waiting to punish him. After the thrashing, the boy halted his nocturnal adventures and became an active member of Christian Union. The school’s orchard was another no-go zone. However, Rop knew that students have appetite for forbidden fruits. The students were always free on Saturday afternoons. Inevitably, the devil had a way of turning our idle minds into his workshop and eventually leading us to the orchard. One Saturday as we harvested the fruits in silence, we heard the grass rustling, yet it was not windy.

We all took off, knowing full well that the deputy head was behind rustle. When we got to the dormitory, we noticed that our fellow fruit thief Sam Mosong had gone missing. Hours later Mosong showed up red-eyed and looking generally battered. He was the unlucky one this time and had run right into the hunter’s hands. “After the slaps and kicks, Mnyaks held me by the scru of the neck and led me to his vehicle. He drove me around the vast school compound and left me at the farthest end and told me if he got to the school dining hall before I did, I would be dead meat,” he narrated. Needless to say, Mosong never liked the sight of fruits until we left Kabarak.

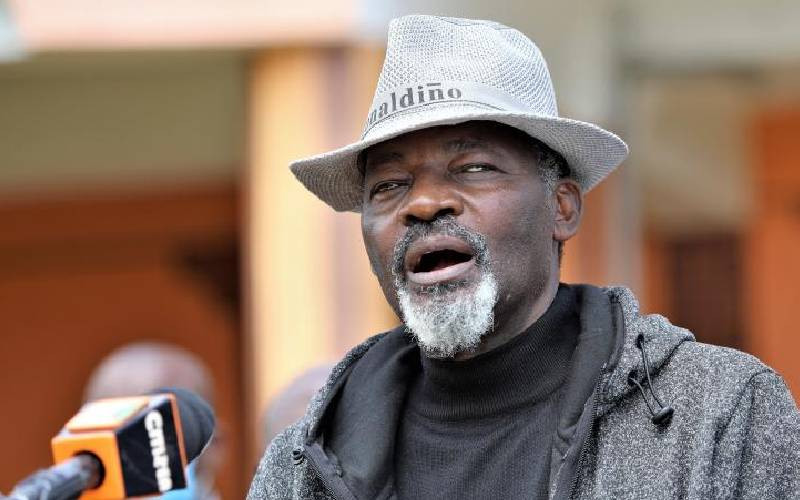

Almost two decades after Rop left Kabarak, I met him at his home in Bombo, Kuresoi Constituency last week. The old man was unapologetic about his severe punishments. “They used to say I was extreme but I was not. I wanted to correct them, shape their characters and weed out the mischief. I wanted them to focus on what brought them to school, not what they loved to do,” he said. Mr Rop, 67, joined Kabarak in 1987 and rose from being a class teacher to a house master and fi nally a deputy principal in 1996. He left for Kericho Tea High school in 2001.

“What made students think I was omnipresent was because I was a fast driver. I could go round monitoring the students in a bus. I would then switch to a car and then another. I even used an ambulance. That is why I always caught them unawares,” he revealed.

In the dormitories and even classrooms, whispering his name could ‘miraculously’ bring him to where you were. Rop said he took time to ‘study’ the behaviour of students. “I always knew their next move s and what they could be doing at a time. I knew there were those who would be sneaking out to steal the fruits and I would just position myself somewhere and make a swoop. I knew there were those who would sneak out to watch TV during preps and I would be there waiting for them to put on the TV,” he said.

Only the most serious indiscipline cases were referred to him by the other teachers. “I always told teachers to deal with indiscipline cases first but when they landed in my office, then I knew that they were difficult cases. Whoever lands there had his shorts removed and was caned properly while wearing only his inner wear,” he added. But despite being tough, the teacher had a soft side. “I still remember Ronald Kibet, a bright but needy boy from Bomet.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

I used to stay with him during holidays because he could not go home. The boy told me he wanted to become a doctor so as to help others. He emerged the top student in Rift Valley in 2000 and is currently a doctor,” he reveals. Rop says he was inspired by former President Moi to be tough. “The President is my great friend and he has put in a lot of e ort in the education sector. He gave his best to the school and that is why I had to play my role in weeding out mischief and indiscipline.”

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.