Teachers are those who use themselves as bridges, over which they invite their students to cross; then having facilitated their crossing, joyfully collapse, encouraging them to create bridges of their own - Nikos Kazantzakis

The report of the Special Investigation Team on School Unrest in 2016 cites congested school routines in some of secondary schools as one of the factors that triggered unrest during second term in the 2016 calendar year.

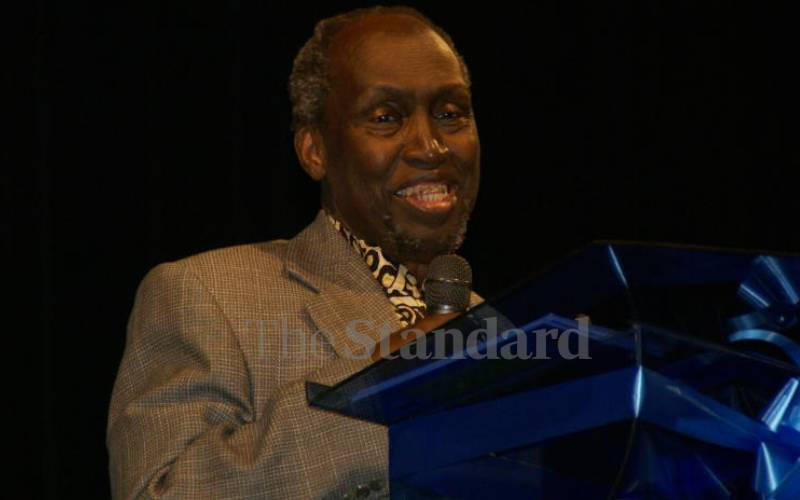

A member of the team, Dr Grace Mullei observed, moments before the report was handed over to Education Cabinet Secretary Fred Matiang’i that in some boarding schools, lessons started as early as 4.30am against Ministry regulations.

A ministry regulation on instructional time prescribes the official school hours for all public and private day primary and secondary schools to be from 8am to 3.30pm.

The import is that as far as possible, there should be no teaching whatsoever before 8am and after 3.30pm. Instead, the period from 3.30pm to 4.45pm has been designated for co-curriculum activities Monday to Friday; while 5.00pm to 7.30pm for self-directed activities Monday to Friday; 7.30pm to 9.30pm preps Monday to Friday; 9.30pm to 6.00am bedtime Monday to Friday; and 6.00am to 8.00am supervised routine activities. Behind the designation of official instructional hours is solid knowledge of educational psychology. In simple language, educational psychology is the study of how humans learn and retain knowledge, primarily in educational settings like classrooms. This includes emotional, social, and cognitive learning processes.

Topnotch organisation of school programmes—including academic programmes—takes into account the knowledge of education psychology. Countries with world outstanding educational systems such as Finland, German, and Japan have provided for instructional time more or less similar to ours.

The running thread on school hours is that the educational system should focus on forming well-founded persons, instead of focusing primarily on intellectual pursuits. Less time tied on a desk could allow students the freedom to discover other interests that are fulfilling and stimulating.

Effective delivery and management of the curriculum is must be based on the ability of learners to be attentive at all times so they can intact with new ideas, concepts and knowledge. This is because a child’s attention span is a very important factor in the learning process. The amount of time a child spends listening and understanding the teacher affects how much he or she has taken from the lesson. That designated instructional hours from 8am to 3.30pm has been broken up into 40 minutes of 8 lessons per day on the ground that effective learning—attention to new educational experiences—happens when we have regulated teaching and learning time, interrupted with short breaks in between lessons and lunch time before the afternoon classes for upper primary and secondary learners resumes.

Tying up children to a desk for long hours under the assumptions of teaching them is counterproductive. It has no basis in educational psychology. It lacks sound logic, to say the least. No matter how good the teacher or how compelling the subject matter — learners suffer from lapses.

Boredom, fatigue and lack of concentration define the moods and minds of learners beyond a maximum number of instructional hours—with or without breaks. When such happens, the minds of students switch off. The teaching that takes place when children are suffering from boredom, fatigue and lack of concentration is a waste of time.

Visibly shocked

One of the things that visibly shocked Dr Matiang’i when he toured some schools that were gripped by unrest during last year’s school calendar was that 16 year old students were forced to wake up as early as 4.30am. He wondered aloud how this could happen when managers of secondary schools studied educational psychology and other units that define, for the prospective teacher, effective teaching and learning environments.

When students wake up as early as that, they probably have not had sufficient sleep, will doze off in class.

They don’t maximise the instructional time as they are not attentive. Psychologists note that children between the ages of 12 to 18 needs at least eight hours of sleep each night, sometimes even nine. Without sufficient sleep, little or no learning takes place as effective learning depends on attentiveness of the learner.

Adherence to the policies of the Ministry on instructional has potential to transform the educational experience that we expose our learners. Educational policies, rules and regulations are the kingpin of delivery of quality education in schools. First it allows teachers more time to plan and think about each lesson. It allows them time to create great, thought provoking lessons for learners, lessons that have the capacity to meet the objectives of every lesson or topic they teach.

Secondly, it enables the teachers to easily transit into the competence based curriculum that the government is in the process of implementing. High quality education is—beyond imparting knowledge—nurtures learning, thinking and life skills of the learners.

The curriculum reform initiative that the government is in the process of bringing about wants to identify and nurture the potential of each child, as well as helping the child determine his destiny. We cannot achieve these goals if all we do is to tie a child on a desk, passively listen to teachers, and take so many examinations with fancy names.

In the delivery of the forthcoming curriculum, students will take charge of their educational adventure.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

Implicit in the recommendation that school management consults relevant stakeholders before setting up changes in programmes is the need for school managements to take into account the fundamentals principles and ideas that underlie positive teaching and learning environments.

Congested school programmes were not the only factor that triggered students’ unrest last year. But addressing this issue will mitigate the unnecessary stress that students bear—stress which provides the ignition for unrest at the slightest provocation.

The writer is Ministry of Education’s Communications Officer

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.