×

The Standard e-Paper

Smart Minds Choose Us

For the third time in three consecutive elections, his proverbial single silver bullet has misfired.

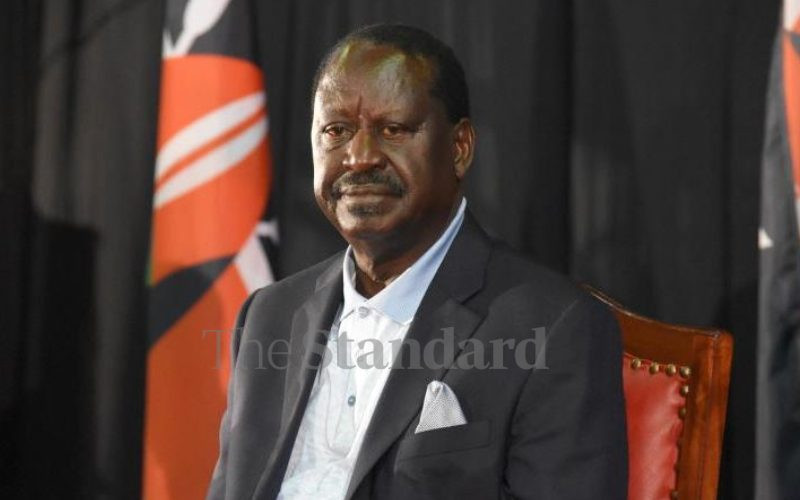

And for the fifth time, Raila Odinga has failed to become the President of Kenya, barring any new developments that could come from the Supreme Court, should he make good the promise to challenge William Ruto's election as Kenya's fifth president on 9 August.