Audio By Vocalize

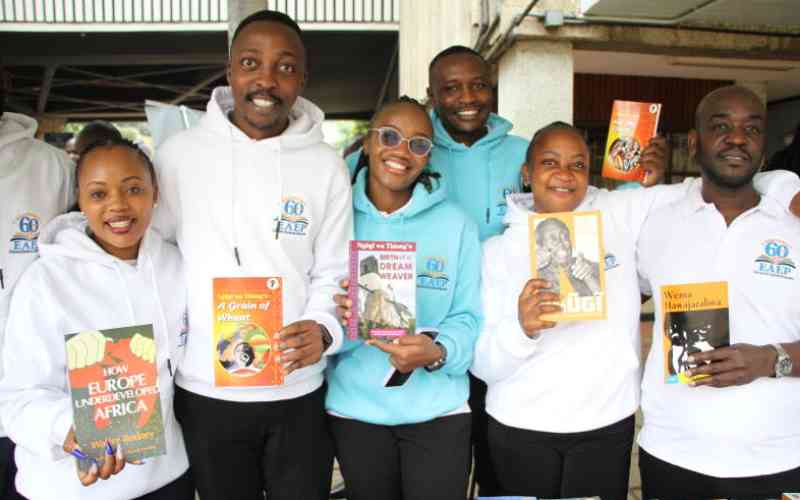

Sometime last month, East African Educational Publishers Ltd celebrated their Diamond Jubilee. I find myself conflicted whenever I have to talk about EAEP.

This is not only because EAEP was my first “permanent and pensionable” employer, but also because the company that started in the 60s as an outlet for books published mainly in London has over the years morphed into one of the major homes of African writing over the past six decades.

That said, this is not about me or my first employer, but rather about the journey African writing has taken over the past six decades.

The African Writers Series has particularly shaped not just how we write about our fears, hopes and aspirations, it has been the architect of the African intellectual universe. Let us put this into historical perspective.

Long before the birth of the AWS, the literary world in Kenya and Africa was largely a microcosm of what has come to be known as the Leavisite tradition. The Leavisite tradition refers to a moralistic literary approach associated with F. R. Leavis, a towering figure in European literary circles.

In his 1948 book, The Great Tradition, Leavis deigned to narrow down the Western literary canon to a handful of authors such as Jane Austen, George Eliot, Henry James and Joseph Conrad. Later, D. H. Lawrence was added to this supposed literary hall of fame.

For Leavis, these writers stood head and shoulders above the rest—not merely for their storytelling, but for their “fine awareness” of the human experience and ethical integrity. In short, they were the works one had to read to learn how to write.

To be fair, Leavis championed close reading to uncover meaning and argued that literature could shield the human spirit from the “noise” of social trends and technological change

Writing at the height of the industrial revolution and its moral anxieties, his position is largely understandable.

The 20th century saw Europe shape Africa in its own image, including literarily. Before the 1980s, African literature students were naturally steeped in the Great Leavisite Tradition, with little fault in that: literature is universal and, at its finest, probes the human experience beyond cultural and historical limits.

Morality—a core Leavisite concern—is shaped by culture and history, revealing the tradition’s flaw. Canonising Jane Austen, for example, imposes one society’s norms globally; canonising Joseph Conrad inadvertently validates the dehumanisation of Africans in *Heart of Darkness*.

This is where the genius of the African Writers Series lies.

The AWS was more than Africans writing their hopes, fears and aspirations. Chinua Achebe, the series’ first editor, said his debut novel, Things Fall Apart (1958), was a response to Conrad’s Heart of Darkness.

The novel deliberately and faithfully portrays the Igbo moral universe.

In that foundational work, Achebe deliberately shows that where Conrad saw darkness, African societies possessed rich linguistic, legal and moral traditions.

Far from a world of bestiality, it was an orderly society governed by justice and moral order—realities that works like Conrad’s, or Joyce Cary’s Mister Johnson, failed to grasp.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

Thus, the AWS was not merely a deconstruction of Africa’s dehumanisation on the page, but rather the immortalisation of an entire way of life that would otherwise have been lost to the world.

The series so profoundly shaped the African literary worldview that it arguably laid the foundation for Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Awuor Anyumba and my friend Taban lo Liyong to anchor the Africanisation of literature studies at the University of Nairobi in the 1980s.

This shift also demanded the courage of publishers like Henry Chakava, who provided a platform at a time when it was widely assumed Africa should read only what came from Europe.

To be clear, literature is not an essentialist social science that seals societies off from others; yet even as a universal discipline, it must localise human experience, for universality arises from humanity’s rich expression across diverse cultural milieus.

Had Africa not offered its own experiences through the works of foundational writers from the continent, we might today believe that there was nothing here in terms of leadership, knowledge or moral order before contact with the rest of the world.

I must hasten to add that I do not necessarily believe Conrad was a bad person, or a thoroughgoing racist. It is human nature to prioritise one’s own experiences, and our intellectual faculties are often limited to the worlds we inhabit.

There was absolutely no way Conrad could have known as much about the Igbo or the Congo as he did about his own society.

It is precisely for this reason that I see his work not as an affront to African ways of life, but as the necessary trigger that gave us not just

Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, but an entire literary cosmos through which we – and the rest of the world – can understand ourselves.

As the African Writers Series marks six decades, gratitude is due not only for the courage of writers who shifted the literary centre from empire to their own worlds, but also for the clarity it has given us about who we are and where we come from.

Nothing captures a people’s history and experience better than an artistic yet authentic portrayal of their society.

Most importantly, there is an urgent need to continue this tradition, not just by publishing works of art that mirror our lives, but by doing so from perspectives that shift timelines, correct misconceptions and shape how we wish to be viewed in the future.

It took great courage to chart that path. It still takes courage to put out epoch-making works of art. We must do so, lest we break a great home-grown tradition and deny our progenitors a cultural record of who we are and where we come from.

As an avid early fan of the AWS, courtesy of the Kenya National Library Service, Embu Branch, I say: long live AWS.