Audio By Vocalize

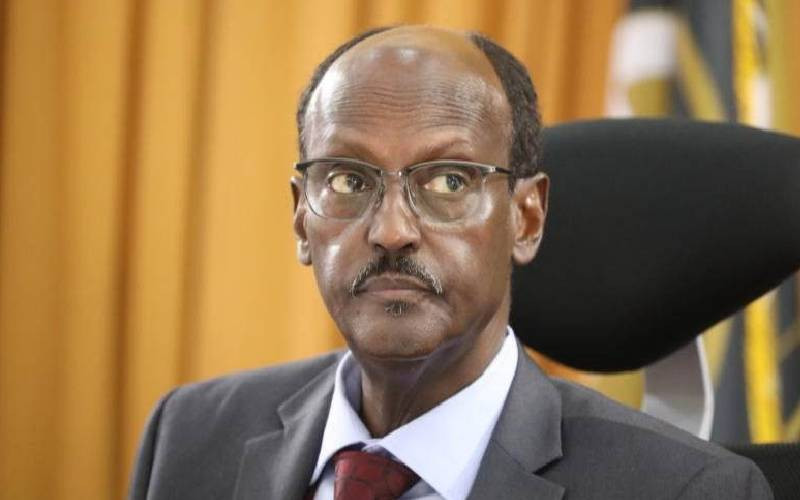

In the annals of Kenya’s constitutional jurisprudence, few names evoke the same quiet reverence and respect as that of the late Mohammed Ibrahim, judge of the Supreme Court of Kenya. His passing is not just the loss of a jurist. It is the departure of a conscience, a moral compass in a judiciary often buffeted by the winds of politics, ideology, and public expectation. He was reserved but unyielding, soft-spoken yet steely in conviction in most of his lone opinions.

Justice Ibrahim’s journey to the highest court in the land was not paved with privilege or ease. His legal philosophy was deeply intertwined with his life’s story, one marked by the struggle against oppression, the scars of detention without trial, and the resilience of a man who refused to be silenced. During the Moi era, Ibrahim stood among those who dared to speak truth to power. He was detained, persecuted, and ostracised but he emerged out of it as a deeply reflective man. He had a profound understanding of the fragility of human rights and the necessity of constitutional safeguards. It was from that crucible that his judicial voice was forged, one that would later echo through his dissents on the Supreme Court bench.

Close to his colleague Justice Njoki Ndung’u in dissents, though distinct in approach. Justice Ibrahim was among the few members of the Supreme Court who consistently exercised independence of thought, unafraid to depart from the majority when conscience demanded it. His dissents were always outstanding, they were reasoned convictions, products of introspection and fidelity to what he believed was the Constitution’s spirit. In a court that often faced the weight of public opinion and political tension, Ibrahim’s jurisprudence stood out for its moral clarity and its rootedness in Kenya’s historical experience.

Perhaps his most enduring judicial moment came in the Building Bridges Initiative (BBI) decision, one of the defining constitutional cases of Kenya’s modern era. While the majority of the bench rejected the introduction of the Basic Structure Doctrine into Kenya’s constitutional framework, Ibrahim stood firm as its lone judicial proponent. To him, the doctrine was no foreign import, but a logical and necessary safeguard born from Kenya’s own painful past. This past to him was that of reckless constitutional mutilation, amendments driven by expediency and the erosion of democratic accountability.

In his view, the Constitution is a sacred social covenant forged in the fires of oppression and sacrifice. To allow its fundamental structure to be amended without restraint would, he warned, open the door to the very abuses that Kenyans had sought to end. “Our history,” he once observed, “teaches us that unchecked amendment power is the first step toward constitutional destruction.” In this dissent, he was profound in tone and prophetic in insight. Ibrahim exhibited the rarest of independence of thought and conscience in a court that has largely normalised unanimous opinions. I do not begrudge the court for that in this piece.

Those who disagreed with his reasoning often acknowledged, even if grudgingly, that his dissent was born out of conscience. Whether on questions of civil liberties and bail, electoral integrity or executive accountability, Ibrahim consistently reflected a commitment to human dignity and the rule of law. He was never one to be swayed by majority sentiments. For him, the law was not an instrument of power, but a shield for the powerless. His dissenting opinions, though sometimes solitary, have since gained respect as beacons of independence of thought. I have seen his colleagues and agemates in the profession describe him as measured, contemplative, and profoundly humane. Behind the quiet demeanor lay a fierce independence of mind, a refusal to bend to external pressures, whether political or institutional. His legal writing carried a rare blend of simplicity and depth, accessible to the ordinary Kenyan at the same time firmly anchored in constitutional theory.

Ibrahim’s legacy is not the number of cases he decided at the Apex Court, but in the integrity with which he decided them. His dissents, much like the great judicial dissents of history, from Lord Atkin in Liversidge v. Anderson to Justice Harlan in Plessy v. Ferguson remind us that the true test of a judge is not conformity but courage. He understood, perhaps better than most judges, that dissent is the lifeblood of jurisprudential discourse and philosophy.

In a judiciary where the temptation for ‘decisional unity’ can sometimes be overwhelming, Ibrahim was different. His jurisprudence was an ongoing dialogue between Kenya’s past and its aspirations, a conversation about what it means to be a just society. In that sense, he was not just a judge of law, but a judge of conscience.

As the nation mourns his passing, it must also reflect on the void he leaves behind. One not easily filled in times when judicial independence faces constant tests. His spirit endures in every lawyer who believes that the law must serve humanity, not the powerful. It endures in every judge who dares to dissent when justice demands it. And it endures in the Constitution he so passionately defended, a document he believed was not merely written, but won in blood.

Justice Mohammed Ibrahim lived by this creed. His legacy is in the bravery of conviction. Through his reasoned solitude, he taught Kenya that justice endures only when conscience outweighs conformity.