×

The Standard e-Paper

Join Thousands Daily

Kenyans have gone gaga that a presidential candidate has grand plans of transforming the country into a billion-dollar drug empire that could challenge the opium fields of Colombia and Afghanistan.

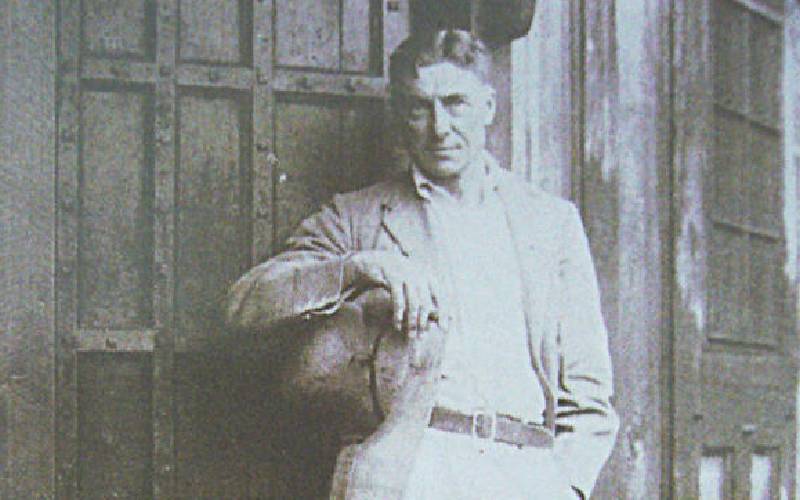

Since he was cleared to contest the presidency, George Wajackoyah of the Roots party has created waves with his promises of establishing commercial farming of bhangi whose final product he proposes to sell and pay off the Chinese debts.