×

The Standard e-Paper

Fearless, Trusted News

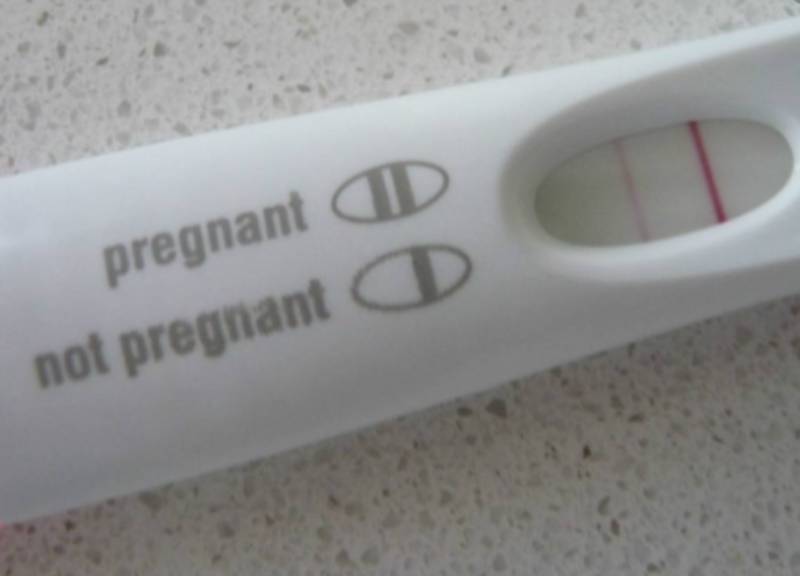

Like for all newlywed couples, life was supposed to follow a certain pattern for Mary when she got married. Get married, enjoy honey moon, get pregnant and enjoy family life. But that was not the case.