×

The Standard e-Paper

Kenya’s Boldest Voice

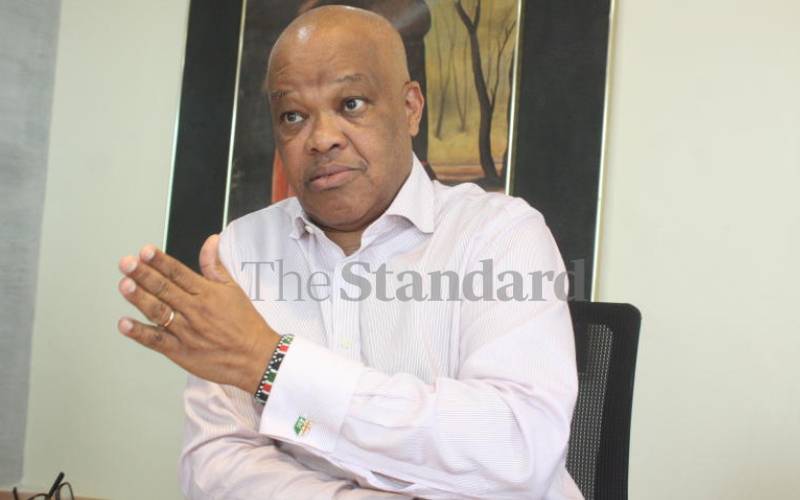

John Ngumi, alongside four partners, birthed the Loita Capital Partners Group in 1994. [David Njaaga, Standard]

John Ngumi, who is credited with brokering deals worth more than Sh1 trillion, survived by eating what he caught in Kenya’s financial jungle.