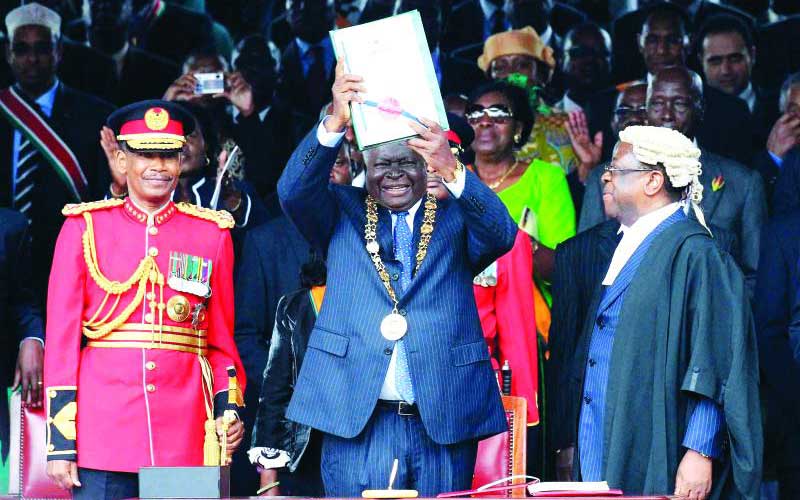

Former President Mwai Kibaki displays the Constitution during its promulgation at the Uhuru Park grounds in Nairobi, August 27, 2010. [File, Standard]

Since it attained Independence in 1963, Kenya has undergone a Constitutional crisis that has lasted decades. The rule of law has been sabotaged, subverted, incapacitated, undermined and alienated at every turn. When Kenya gained Independence, it inherited and worsened the colonial crisis of governance with dire infringements on human rights and calamitous consequences on its economy.