Another African strongman has slept. Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali of Tunisia died on Wednesday this week in exile in Saudi Arabia. He joined several other African strongmen who have died in disgrace in exile. Outstanding among them are Mobutu Sese Seko of Zaire, Idi Amin of Uganda and Milton Obote also of Uganda. There are others.

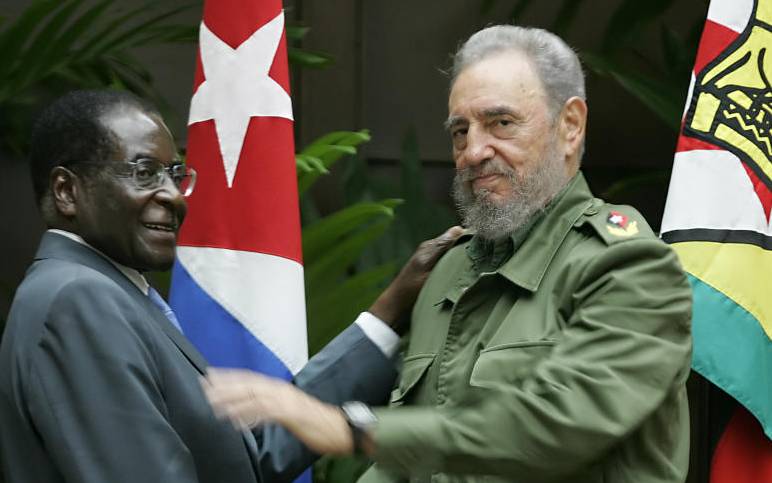

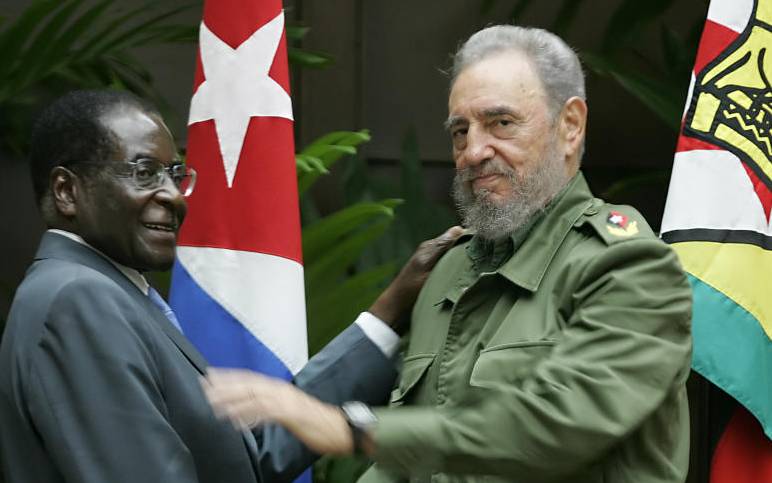

Mobutu, Amin, Obote and Ali have some uncanny political resemblance. Together with Robert Mugabe who is set to be buried in Harare in about a month’s time, they embody a great African paradox. When they came to power, each of them brought great hope and relief in their countries. They rose to power in times of great uncertainty and anxiety. Their people saw them as messiahs. Yet they left the centre of power dishonored.

Obote was among the harbingers of African independence. Mugabe delivered Zimbabwe from the façade that was the Zimbabwe-Rhodesia confederacy of Ian Smith and Bishop Abel Muzorewa. Idi Amin was celebrated in the streets of Kampala and beyond for ending the murderous regime known in Uganda as Obote I. Mobutu was a sigh of relief for a greatly troubled and confused Congo Kinshasa, courtesy of the power struggles between Patrice Lumumba and Moise Tshombe. Yet they each deteriorated very steadily, once in power. The lasting legacy of each of these men is that of disgraced dictatorship.

Ben Ali came to power in 1987, following a “palace coup” in Tunisia. He led the military in declaring the long-serving independence President, Habib Bourguiba, as mentally unstable. He was unfit to rule, they said. The world heaved a sigh of relief with Tunisia. The tyrant who had been in power for 22 years was gone. In Tunis, everyone wanted to kiss Ben Ali. Little did they know he would preside over a police state for 23 years. Ben Ali eventually fell to the Arab Spring in 2011. He fled to Saudi, where he died this week.

Ben Ali will be remembered for corruption and tight control on political and economic power. He presided over the kind of hopelessness that saw young men set themselves on fire in Tunis, to protest against political corruption, tight control of the media, poor living standards and abuse of human rights everywhere.

This legacy overshadows Ben Ali’s initial reformist agenda and the economic stability that he brought to Tunisia after Bourguiba. People like Ben Ali remind us that there is no heroism in someone claiming to liberate you from oppression only for him to become the new oppressor.

As Ben Ali goes to rest, his country reminds us of Africa’s fall from grace to grass through millennia. It also reminds us of the long delayed African renaissance. Each time there is a whiff of freshness anywhere on the continent, citizens hold their breath in the hope that it could be the start of the long-awaited African rebirth. For, Tunisia is the phoenix that rose from the ashes of the historical Carthage.

Students of history will remember the famous oratorical refrain, “Carthage must be destroyed.” It was Cato the Elder (234 – 149 BC) who made famous this chorus, “Carthago delenda est.” Cato used this expression in the Roman Senate of his day, to urge for war against the indomitable African state of his day.

It was from Carthage that the great General Hannibal led African armies across the Mediterranean Sea on elephant back to Europe. Hannibal’s gallantly marched on to Rome and occupied her for 15 years. The gallant Carthaginians eventually fell in what is today Spain, under the hand of the superior command of Scipio Africanus of Rome in the Second Punic War. Historians tell us that when Cato the Elder visited Carthage later, he was amazed to see how wealthy and organised the Africans were. He was convinced that they would reassemble and overrun Europe. This was unless Carthage was destroyed. And destroyed it was. The Romans razed it to the ground in the Third Punic War (149 – 146 BC). Not far from Tunis, the ruins remain as a tourist attraction.

What the Romans did not do elsewhere on the continent we have done ourselves. Our great past is preserved in Robin Walker’s great book titled, When We Ruled. Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson will meanwhile tell you why we are the cesspit of the world today. In their volume titled The Origins of Power, Prosperity and Poverty: Why Nations Fail, the two scholars remind us that it is not our climate or location that makes us sick, poor and starved. Our leaders abuse political power, and we allow them to do so. They have created a vicious circle in the relationship between politics and economics. They use each to control the other. The citizens are the pawns in these political and economic power games.

Poet Niyi Osundare has called them “the reptiles of state.” And they seem to like it that way. Emmerson Munangagwa of Zimbabwe calls himself “the crocodile.” Every so often, one crocodile is kicked out, Bourguiba style. Another one like Munangagwa will take over. Like I concluded in this space last week, Africans must ask themselves why they allow this to happen. Meanwhile, there can be no tears to shed for these African crocodiles. The veritably empty stadium in which African leaders outdid each other in lavishing Mugabe with empty praise should tell them something. Where were the people?

- The writer is a strategic public communication adviser. www.barrackmuluka.co.ke

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.