×

The Standard e-Paper

Fearless, Trusted News

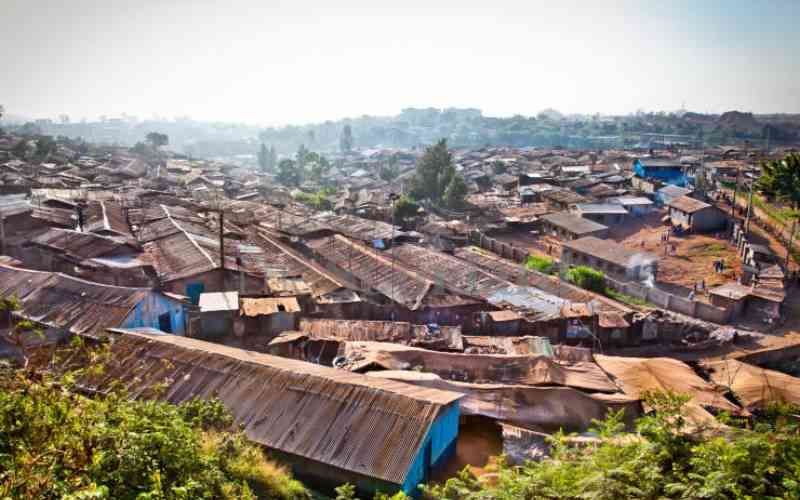

Residents of informal settlements are exposed to worrying levels of air pollution, new scientific research shows.

A two-year study in Mukuru, Kenya, and Ndirande, Malawi, found that charcoal and firewood for cooking emit toxic pollutants that pose severe health risks.