×

The Standard e-Paper

Stay Informed, Even Offline

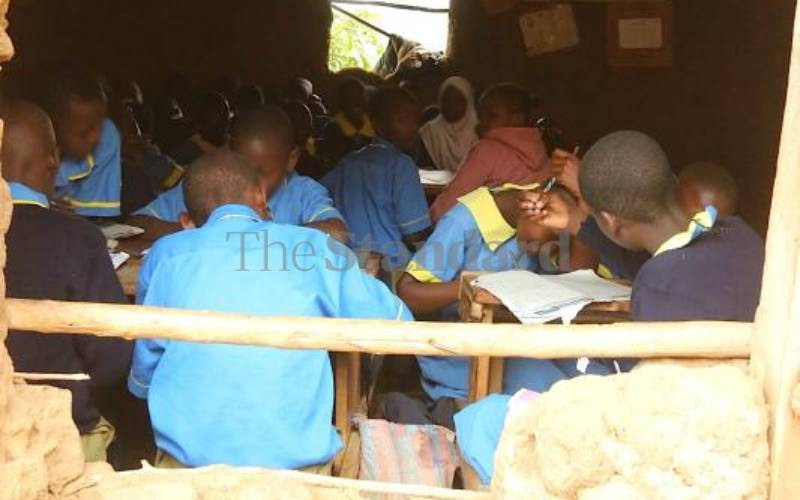

The UN calls World Children's Day a day "to advocate, promote and celebrate children's rights". And key among those is the right to education. Superficially, states have made great progress in ensuring this right is realised. Decades of enrollment drives mean that around 90 per cent of primary-age children are in school.

But to have any meaning, the right to education must ensure learning. For most children around the world, including Kenya, it does not.