×

The Standard e-Paper

Smart Minds Choose Us

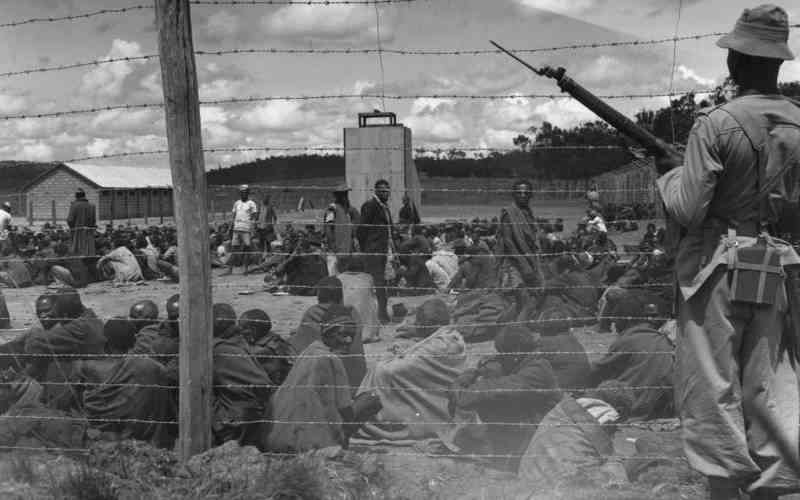

As millions around the world mourn the death of the world's second longest reigning monarch, Queen Elizabeth II, her exit has triggered dark memories of some of the travesties executed in her majesty's name in parts of Africa.

Had Queen Elizabeth ruled for three more years, she would have beaten the record set by Frances King Loius XIV, who reigned for 72 years and 110 days from 1643 to 1715.