×

The Standard e-Paper

Join Thousands Daily

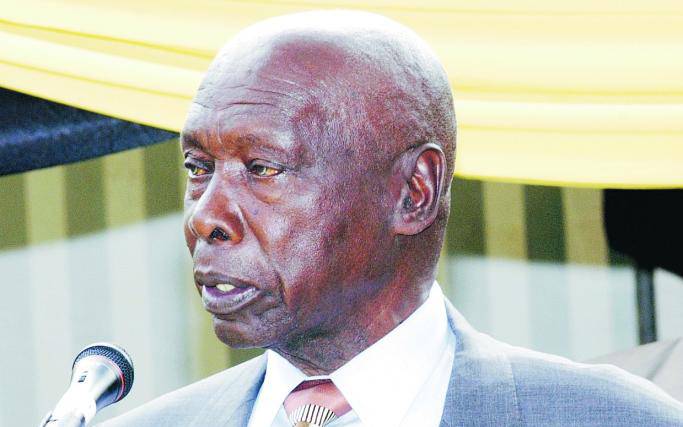

Former president Daniel Moi addressing the media in a past event. He will be buried at his home in Kabarak on Wednesday next week. [File, Standard]

Talking to a few members of the family of the late President Daniel Toroitich arap Moi over the past few weeks, one could barely discern that Mzee’s life was on the precipice.