×

The Standard e-Paper

Stay Informed, Even Offline

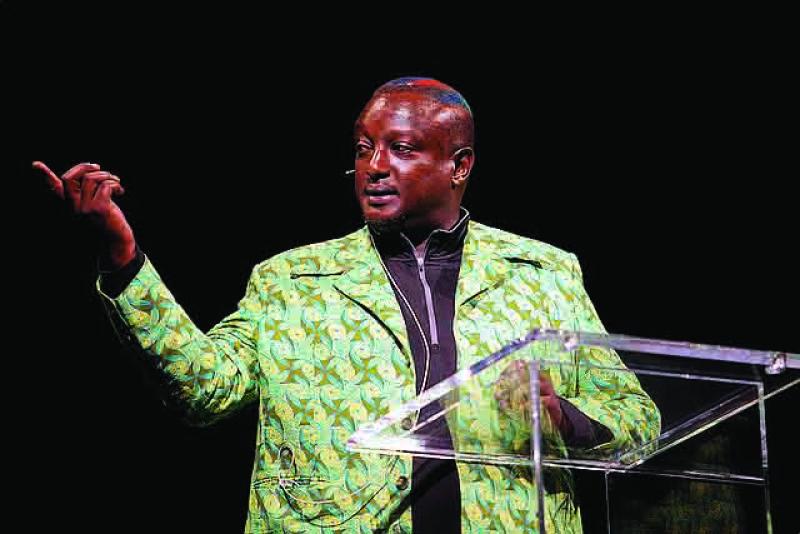

He represented a new generation of Kenyan writers who forced their way onto the literary landscape at the turn of the century, winning a Caine Prize for Africa Writing in the process

He was a great Kenyan. Like Chinua Achebe before him, Binyavanga will be remembered for helping to initiate and promote literary production by a new breed of Kenyan and African writers.