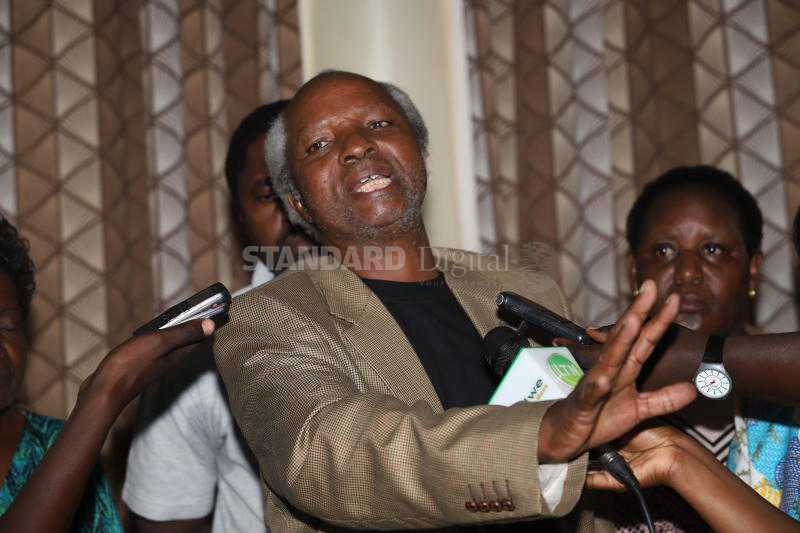

The existence of an African Parliamentarians Network against Corruption (APNAC) is one of the bad jokes in Africa. Of course, it is a pun that dates back to 1999 when it was conceived as a noble cause by Westerners for Africans, except that the latter's perspective on corruption is totally different. It astounds that our National Assembly Speaker, Justin Muturi, while presiding over the parliament should promise to end corruption in Africa and improve the living standards of the continent’s indigent after being elected President of APNAC.

African countries have the pride of place in the top ranks of corruption worldwide. Transparency International's Corruption Perception Index, having ranked 180 countries in 2017 on a scale of 0 - 100, gave African countries a mean score of 32. Corruption is a way of life in Africa, and those perfecting it are its leaders. They have no reason to fight corruption when they are the biggest beneficiaries.