×

The Standard e-Paper

Kenya’s Boldest Voice

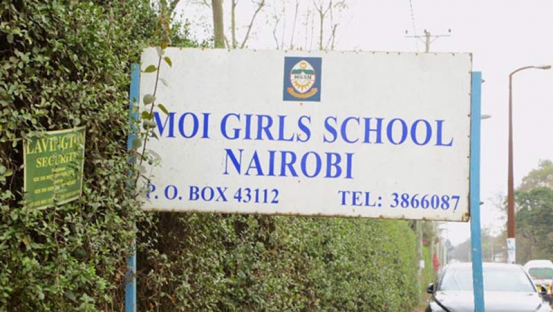

The recent spate of accidents, fires and building collapses reflect a country that is sleeping at the wheel. Listening to the conversations after the horrific fires in Moi Girls and Sigoti Secondary schools and the terrifying Thika road accident, we seem caught in reactionary blame-games that finds fault either in Government or the public.

Is it time for us to revisit the role of citizens, civic organisations, public and private institutions in law enforcement, fire-services and health emergencies?