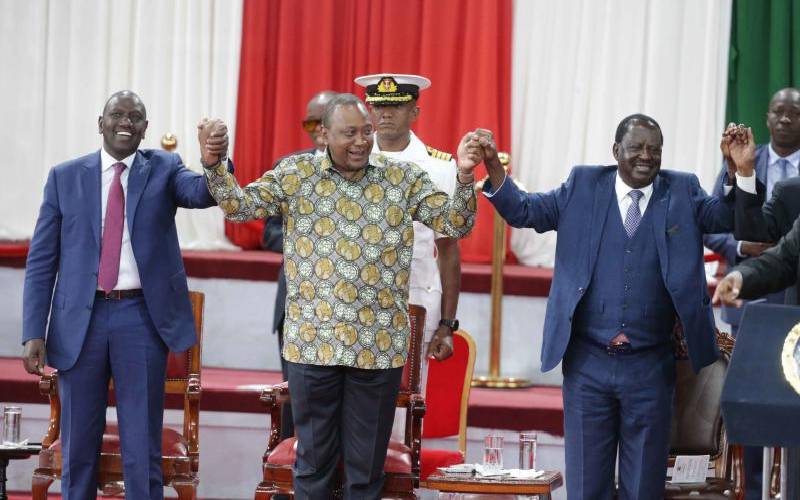

Recently the concept deep state has sauntered into our political lexicon with razzmatazz. To hear Deputy President William Ruto and his supporters’ frequent invocations of the deep state, you get the spooky feeling that there is a secret army of malcontents lurking deep within the bowels of government whose goal is to vehemently curtail his presidential ambitions.

On the other hand, former Prime Minister Raila Odinga and his coterie are accusing Ruto of splitting hairs to find an excuse to reject the outcome of the 2022 presidential elections. They add that as DP he is, in fact, the embodiment of the deep state. Is Ruto chasing his own tail?