×

The Standard e-Paper

Smart Minds Choose Us

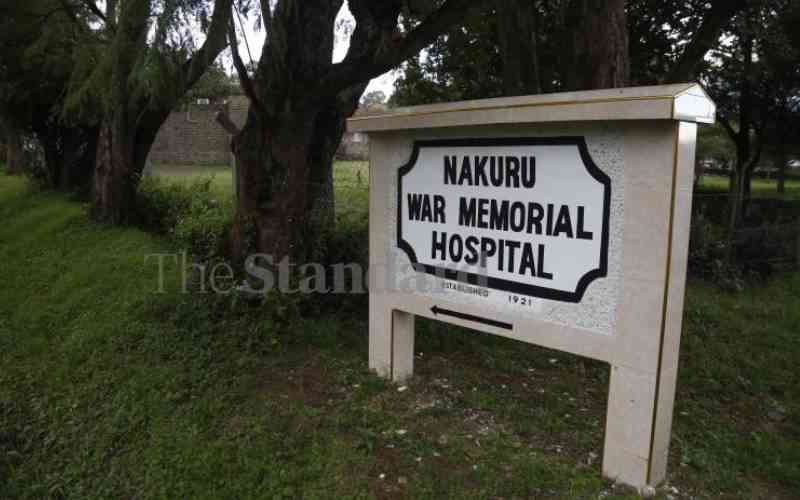

Attempts by the County Government of Nakuru to forcefully take land on which War Memorial Hospital stands introduces another twist in the 50-year-old controversy over the ownership of the medical facility.