×

The Standard e-Paper

Smart Minds Choose Us

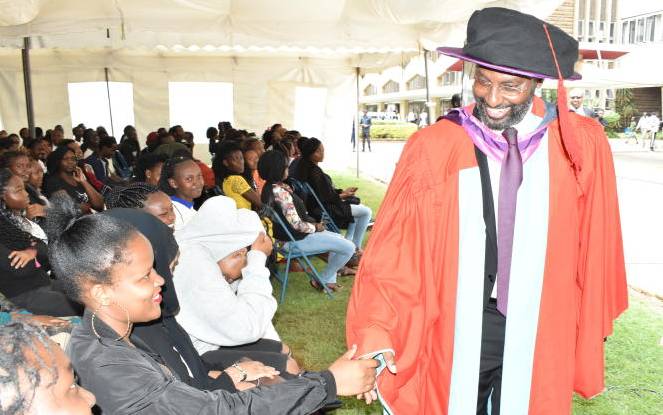

UoN Vice-Chancellor Prof Stephen Kiama shaking hands with students of Nairobi University during the orientation and day of giving Vice-Chancellor welcoming speech to students from the college of Social Sciences and Humanity. [Samson Wire, Standard]

The push and pull that followed the appointment of Stephen Kiama as Vice-Chancellor (VC) of the University of Nairobi (UoN) cast a spotlight on the process of hiring top varsity managers.