×

The Standard e-Paper

Kenya’s Boldest Voice

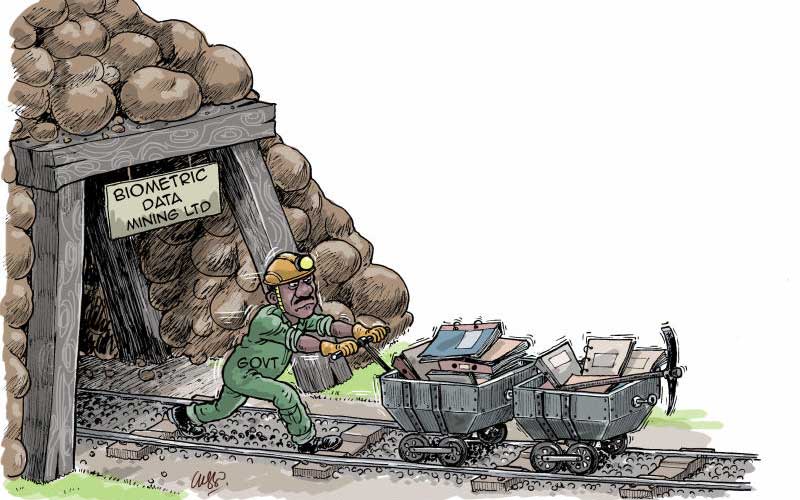

On July 31, I had the unenviable honour of attending a public participation forum on the newly proposed Huduma Bill 2019. Like most important forums, it was scantily attended. Jaded officers from the Ministry of Interior listened to civil society representatives outlining rather obvious shortcomings in drafting of the bill in question, as well as glaring potential for human rights violations.