×

The Standard e-Paper

Home To Bold Columnists

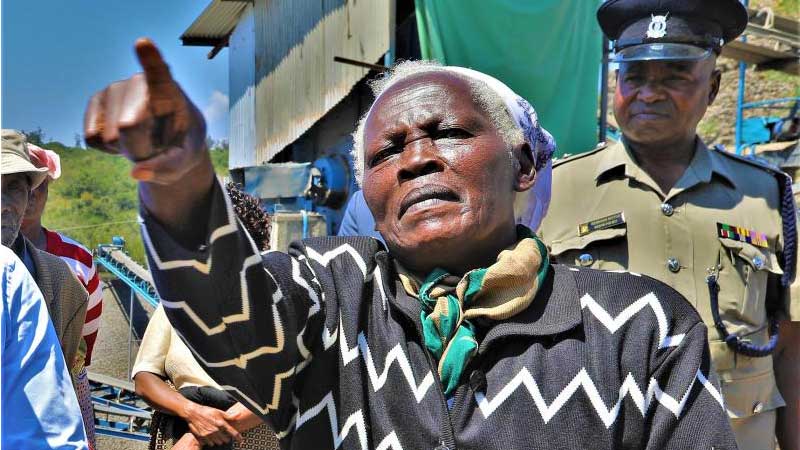

Lydia Gachambi detests the hot weather.

She is her late 70s and walks with the aid of a cane because her joints are afflicted with arthritis, but she prefers the cold season even though she suffers more.