Almost three decades ago, an ambitious Kenya unveiled locally made cars in an aim to take a share of Japan’s grip on the world’s auto-manufacturing market.

Foreign exchange would pour into the country like waters of the Athi emptying into the Indian Ocean, declared a newspaper supplement.

Anxious Kenyans and doubting Thomases, trooped to the Moi International Sports Centre, Kasarani to witness former President Moi inaugurate ‘Kenya’s miracle’.

It was hard to pin down their exact mood because a few days earlier, slain Foreign Affairs Minister Dr Robert Ouko, a key economic draftsman, had been buried.

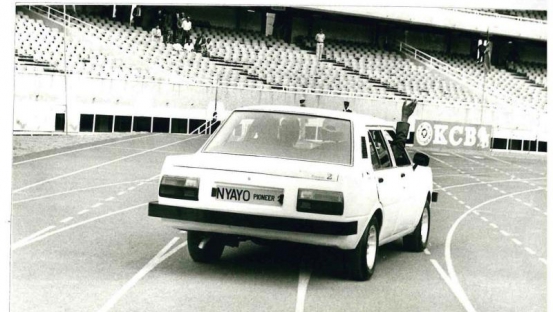

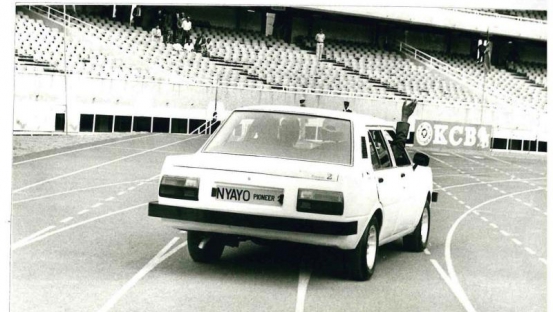

President Moi finally presented two saloon cars and a pickup dubbed Nyayo Pioneer One, two and three.

It was a culmination of a four-year labour following Moi’s challenge to the University of Nairobi in 1986 to produce a car “however ugly or slow it may be.” Five prototypes were made.

The development of the engine block alone took 20,000 man hours, 60 per cent of which were spent on pattern design.

The saloon cars had a maximum speed of 120km/hr, with an engine capacity of 1300cc, four cylinders and a seating capacity of five people.

The pickup packed a speed of 100km/hr, with the same engine capacity as the saloon cars and cylinders. The cars had been borne out of sheer patriotism, with Moi heavily investing in the project.

Earlier in 1988, he had test-driven a prototype which didn’t quite impress him. Unveiling them was the crowning moment for ‘Made in Kenya’ products. “Even if they are ugly, they are ours,” a triumphant Moi told the crowd at Kasarani. He even set aside land that was to house the factory and an assembly line to manufacture the Nyayo Pioneer cars.

A company would also be formed to oversee the project and a reputable car manufacturing firm would be allowed to buy five per cent shares.

The rest of the shares would be sold to the public, he said. The President was then shown the various components used in the car such as the engine block, electrical parts and carburettor, all bearing ‘Made in Kenya’ signs.

He then got behind the wheels of Nyayo Pioneer Two and drove it along the tracks to cheers from wananchi, diplomatic corps, MPs, cabinet ministers and senior civil servants, as reported by The Standard on February 28, 1990.

However, it is reported, that the car did not move past the 400-metre mark. Interestingly, Prof Francis Gichaga, a former Vice Chancellor of the University of Nairobi who was involved in the project, said that the car that refused to move during the launch belonged to the late Nicholas Biwott.

Assembly line

‘Total Man’ had ordered that they hurriedly produce a pick up for him to coincide with the launch.

Moi hinted that upon completion of the factory and assembly line, 3000 units would be manufactured annually. This would however be increased up to 100,000 units a year.

The per unit cost of producing a saloon car was about Sh160,000. He said the market for transport vehicles was expected to grow in the decade.

“In this regard, it is important that in the near future, a reasonable proportion of this market be supported by our Kenyan made saloon cars and light commercial vehicles,” he said.

They would be the cheapest new vehicles in the market due to reduced reliance on expensive imported components and increased use of existing industrial potential in the country, he added.

The project continued with the formation of the Nyayo Motor Corporation. The government also planned to establish 11 plants at a cost of Sh7.8 billion. This too failed as it only managed to form the General Machining Complex.

The corporation is currently known as the Numerical Machining Complex.

The University of Nairobi, the Kenya Railways Corporation, the Department of Defence, the Kenya Polytechnic, the National Council of Science and Technology and the Ministry of Industry, all collaborated in the car making venture.

UoN had to borrow facilities from Kenya Railways Engineering workshop where fabrication was done routinely to fabricate the engine and its components, gearbox and transmission system.

The media also played a huge part in hyping the new era of industrialisation. “Good morning Japan. Kenya is racing to catch up with you,” wrote the Standard after the unveiling. The paper, however, warned Japan not to panic. “Kenya is still going to import cars from that country for some time but what is certain is that the import of Japanese cars will go down once the proposed factory and assembly line to manufacture the Kenyan car becomes a reality.” But it warned Japan that the message was loud and clear.

Kenya had developed a car and would use its technology to perfect it so that it can compete effectively with car models in the world market. Many commentators, however, observed that the project was conducted in mystery.

Locally made

Except from statements by then UoN Vice Chancellor Prof Phillip Mbithi that the cars were made locally, no tangible data or specification of a technical nature was forthcoming, wrote one motoring columnist.

He also said that the probing eyes of journalists were shuttered when a display of the locally produced parts, from semi-finished to fully machined stages, was quickly covered by a large white veil during the inauguration of the vehicles. “No more questions and no more answers,” he wrote.

They were only informed that the cars had satisfied the local specifications including those set by the Kenya Bureau of Standards. The government remained proud of these cars calling them “Kenyan made beauties” in advertisements.

A supplement in The Standard declared that Kenya was on the verge of becoming a popular auto manufacturer in Africa in that decade. “Predictably, interested buyers will come from all parts of Africa and outside to make enquiries,” it said.

“Wholesale buyers will converge at one of the Pioneer car factories, while small scale clients will settle for dealers and agents.”

The 1990s also saw Kenya take a stab at manufacturing tractors. In 1991, Jomo Kenyatta University of Science and Technology launched a hand driven tractor which after initial tests in field conditions at various speeds and at various ploughing depths recorded a 15cm depth.

The average rate of work for the tractors was found to be between 0.02 and 0.06 hectares per hour.

But the dream for a locally made car has never faded.

In 2014, Mobius, a Kenyan-made vehicle touted to be Africa’s cheapest car at Sh950,000, hit the market.

The car is made by Mobius Motors and assembled by Thika-based Kenya Vehicle Manufacturers. Official data, however, shows that the assembly of motor vehicles, trailers and semi-trailers fell by 26.7 per cent in 2016.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print operations, television, radio broadcasting,

digital and online services. The Standard Group is recognized as a leading

multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and

international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print operations, television, radio broadcasting,

digital and online services. The Standard Group is recognized as a leading

multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and

international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print operations, television, radio broadcasting,

digital and online services. The Standard Group is recognized as a leading

multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and

international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print operations, television, radio broadcasting,

digital and online services. The Standard Group is recognized as a leading

multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and

international interest.